The AMO Model Explained: Ability, Motivation and Opportunity in HR

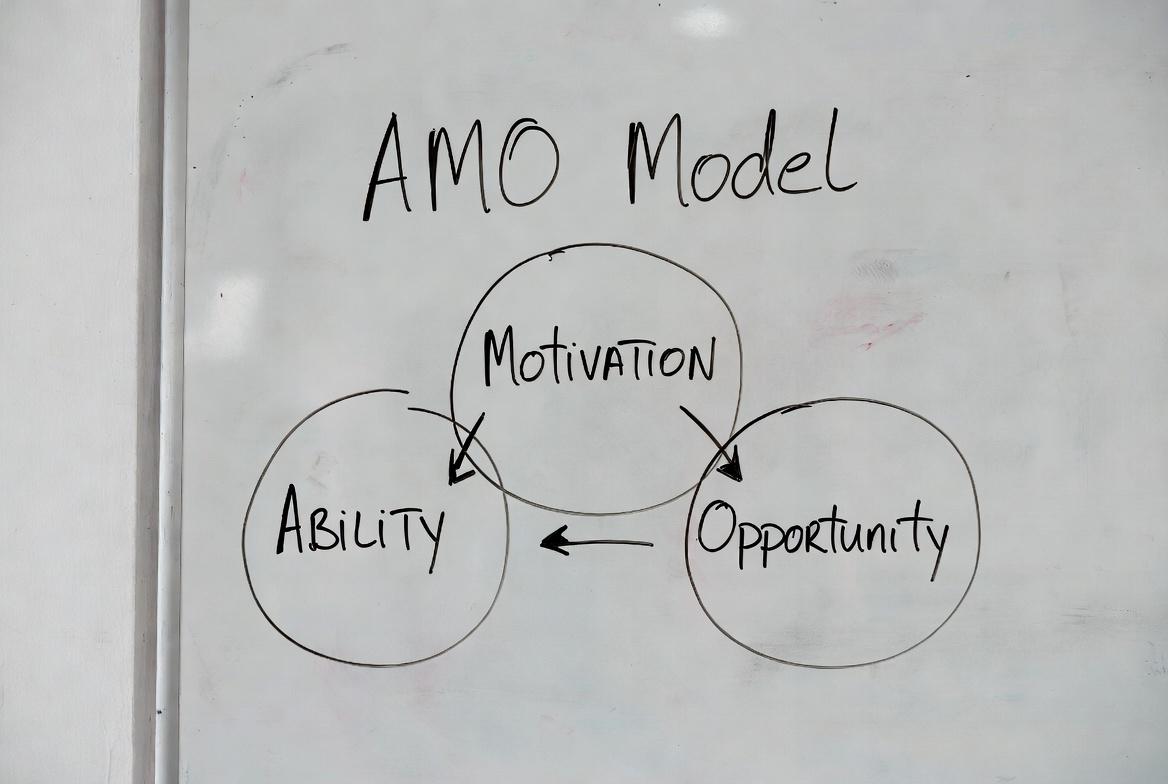

The AMO model provides one of the clearest explanations for why some employees perform better than others. Developed by Appelbaum and colleagues in 2000, it proposes that individual performance is a function of three elements: ability (can they do it?), motivation (will they do it?), and opportunity (do they have the chance to do it?). When all three are present, performance flourishes. When any one is missing, performance suffers regardless of how strong the others might be.

This framework has become central to understanding high performance work systems and appears frequently in CIPD qualifications, particularly when discussing performance management, learning and development, and HR strategy. Its elegance lies in its simplicity—three variables that explain a complex phenomenon—while still offering practical guidance for HR interventions.

Understanding the Three Components

Ability

Ability refers to whether employees possess the knowledge, skills, and capabilities required to perform their roles effectively. This encompasses both the technical competencies specific to a job and the broader capabilities that enable someone to work well in an organisational context.

HR practices that enhance ability include rigorous recruitment and selection processes that identify candidates with the right capabilities, comprehensive induction programmes that build role-specific knowledge, ongoing training and development that keeps skills current, and talent management approaches that develop future capabilities. When organisations invest in ability, they're essentially ensuring that employees have the tools to do what's asked of them.

The ability component reminds us that motivation alone is insufficient. An employee might be deeply committed to their work and have every opportunity to contribute, but if they lack the necessary skills, their performance will fall short. This is why skills gaps represent such a significant challenge—they create a ceiling on what individuals can achieve regardless of how hard they try.

Assessing ability requires honest evaluation of what roles actually demand versus what employees can deliver. Job analysis helps identify required competencies. Skills audits reveal gaps between current and needed capabilities. Performance data shows where ability shortfalls manifest in practice. This diagnostic work should inform decisions about training investment, recruitment priorities, and job design.

Motivation

Motivation addresses whether employees choose to direct their effort toward organisational goals. Having the ability to perform is meaningless if someone doesn't want to use it. Motivation theories—from Maslow's hierarchy to Herzberg's two-factor theory to more contemporary approaches—all attempt to explain what drives this willingness to contribute.

HR practices that enhance motivation include reward and recognition systems that make effort worthwhile, performance management processes that provide feedback and direction, job design that creates meaningful and engaging work, and leadership practices that inspire commitment. The common thread is creating conditions where employees see value in investing their energy.

Motivation is inherently personal. What drives one employee may leave another indifferent. Financial incentives matter to some; recognition and achievement matter more to others. Autonomy energises certain people while overwhelming others. Effective motivation strategies recognise this diversity and offer varied pathways to engagement rather than assuming one approach fits all.

The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation matters here. Intrinsic motivation comes from the work itself—finding it interesting, meaningful, or enjoyable. Extrinsic motivation comes from outcomes associated with work—pay, promotion, recognition. Both matter, but research suggests intrinsic motivation tends to be more sustainable and leads to higher quality performance. HR practices should attend to both, but creating intrinsically motivating work often delivers greater returns.

Opportunity

Opportunity refers to whether employees have the chance to use their abilities and apply their motivation. This is the element organisations most often overlook. Someone might be highly capable and deeply motivated, but if organisational structures, processes, or culture prevent them from contributing, their potential remains unrealised.

HR practices that enhance opportunity include participative decision-making structures that give employees voice, job designs that provide autonomy and discretion, communication systems that share information employees need, and cultures that encourage initiative rather than punishing deviation from norms. Opportunity is about creating space for contribution.

The opportunity component highlights how organisational context shapes individual performance. Rigid hierarchies that concentrate decision-making at the top limit opportunity regardless of workforce capability. Micromanagement that removes discretion from roles constrains what motivated employees can achieve. Information hoarding that keeps people in the dark prevents them from contributing their knowledge. These structural factors often matter more than individual characteristics.

Opportunity also connects to workload and resources. Employees who are overwhelmed with tasks lack the opportunity to perform any of them well. Those without adequate tools, technology, or support cannot translate ability into results. Creating opportunity means ensuring people have what they need to succeed, not just permission to try.

How the Components Interact

The AMO model's power comes from recognising that performance requires all three elements working together. This isn't simply additive—it's multiplicative. If any component approaches zero, performance approaches zero regardless of the others.

Consider a highly skilled employee (high ability) who is deeply committed to their work (high motivation) but works in an organisation where decisions are made without their input and initiative is discouraged (low opportunity). Their performance will disappoint despite their capability and willingness. The constraint isn't the person; it's the context.

Or consider someone given significant autonomy and voice (high opportunity) who genuinely wants to contribute (high motivation) but lacks the knowledge and skills the role demands (low ability). Their enthusiasm and their organisation's openness cannot compensate for the capability gap.

This multiplicative relationship has important implications for HR strategy. Investing heavily in one component while neglecting others produces limited returns. Training programmes (ability) matter little if employees aren't motivated to apply what they learn. Engagement initiatives (motivation) achieve little if organisational structures don't let people contribute. Empowerment efforts (opportunity) flounder if people lack the skills to use their autonomy effectively.

Diagnostic work should assess all three components before deciding where to invest. Sometimes the binding constraint is obvious; sometimes it requires careful analysis. The AMO framework provides a structure for that analysis and helps avoid the common mistake of addressing the wrong problem.

Applying AMO to High Performance Work Systems

The AMO model emerged from research into high performance work systems (HPWS)—bundles of HR practices that, when implemented together, produce superior organisational performance. The model helps explain why these systems work and guides their design.

High performance work systems typically include practices addressing all three AMO components. Selective hiring and extensive training build ability. Performance-related pay and involvement in decision-making enhance motivation. Self-managed teams and information sharing create opportunity. The bundle works because it attends to all three requirements for performance.

Research consistently shows that HPWS outperform traditional approaches, but implementation is uneven. Many organisations adopt some practices while neglecting others, reducing effectiveness. The AMO model explains why partial implementation disappoints—missing components create bottlenecks that limit what the present components can achieve.

When evaluating or designing HR systems, the AMO framework provides useful questions. Which practices enhance ability? Which build motivation? Which create opportunity? Are all three adequately addressed? Where are the gaps? This systematic approach helps ensure coherent systems rather than collections of disconnected practices.

Using AMO in CIPD Assignments

The AMO model offers a valuable analytical framework for CIPD assignments. When asked to evaluate performance issues, recommend HR interventions, or analyse case studies, AMO provides structure for your analysis.

Start by diagnosing which component or components are deficient. Is the problem that employees lack necessary skills? That they're not motivated to perform? That organisational barriers prevent contribution? Often multiple components are involved, but identifying the primary constraint helps prioritise interventions.

Then consider what practices would address the identified gaps. Be specific about how particular interventions connect to ability, motivation, or opportunity. Generic recommendations lack the analytical depth assessors look for; showing how your proposals address specific AMO components demonstrates sophisticated thinking.

Remember to consider interactions between components. Acknowledge that addressing one element may require attention to others. Training programmes (ability) work better when accompanied by opportunities to apply new skills. Empowerment initiatives (opportunity) require capable employees who understand how to use their autonomy. This systems thinking distinguishes strong assignments from superficial ones.

Compare AMO with other frameworks where appropriate. How does it relate to motivation theories you've studied? How does it connect to strategic HRM perspectives? These connections demonstrate breadth of knowledge and ability to integrate different concepts.

Critiques and Limitations

While widely used, the AMO model has limitations worth acknowledging in your assignments. Critics note that the model treats the three components as relatively independent when in practice they interact in complex ways. Motivation affects how people develop ability; opportunity shapes what motivation means in practice.

The model also focuses on individual performance without fully addressing how individual contributions combine into team and organisational outcomes. High individual performance doesn't automatically translate into collective success—coordination, collaboration, and alignment matter too.

Some scholars question whether the relationship is truly multiplicative as the model suggests, or whether the components combine in more complex, context-dependent ways. The elegant simplicity of A×M×O may oversimplify reality.

Despite these limitations, the AMO model remains valuable as a diagnostic and planning tool. Its clarity helps structure thinking about performance, even if reality is messier than the model suggests. Used thoughtfully, with awareness of its limitations, it provides genuine insight into why performance varies and what organisations can do about it.